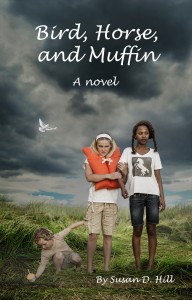

Hello readers! For my post this week, I am sharing the opening scenes of my award-winning novel, Bird Horse, and Muffin, a story of finding God in the midst of loss. Keep in mind that all the God moments in this novel are based on true stories. Write me if you’d like a signed copy…

Prologue…

I am not old, but I’m no longer a child. Sometimes I’m brave enough to think about those days—days of suffocating fear and weeks when sadness had no end, and I lived with many questions tapping on my brain like a relentless woodpecker. Each new bend in the road of twists and turns thrust me into the unknown like a wild mustang ride…snorting, stomping, and even trampling my simple world. And when the quiet came at night, my heart seemed as cold as the bottom of the great lake.

Yet Nana’s gentle hand on my arm, or the look in Skeets’ kind eyes, well, they kept something muffin alive in me. They made me believe a greater thing could happen, something I’ve never quite been able to explain—that calm knowing inside, the surge of boldness I felt and the certainty of where it was from. I sometimes wonder at how easily I could have ignored it. I could’ve been distracted and missed it.

But I didn’t. Somehow, I didn’t.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Chapter

How graceful is your grace?

The first time I heard God speak was in a school parking lot. I was ten years old.

My heart flipped violently. The words were unmistakable, as if He stood right behind me and whispered in my left ear. I twirled a complete circle but found no one.

Chills rippled across my skin like electric current. I sank to my knees. God sounded calm. Still I gasped, because Mama said He didn’t lie. A perfect summer day had become a muted fuzzy dream.

The morning had started with warm rays through my bedroom window and the fresh earth smell that follows a summer rain. I bounded down the stairs like a cat that smells tuna in the air, but I stopped short on the landing.

Our only happy-family picture hung on the wall, slightly askew. I tilted my head. There, in black and white, we huddled on our sailboat with the mainsail for a backdrop. The wind had played with our hair, and we were all smiles. Grace, or Mama as we called her, held my little brother Tuck on her hip. My older brother Wyeth posed behind me. He made bunny-ears at the back of my head, which he later claimed was just a peace sign. Being the only girl, I remained an easy target. Our father, Hank, looked rather handsome but towered over us with a firm grip on the tiller. Somehow, his smile didn’t belong to his face.

My chest tightened. I turned away.

The sound of running water in the kitchen sink spread uneasiness through my body. I always calmed myself down before entering the kitchen, because it was Father’s Command Central in the mornings. He had a set routine—making his coffee just so, arranging his spoon, sugar bowl and Cleveland Indians mug in a line on the counter. He’d lay The Plain Dealer on the table with a freshly sharpened pencil for the crossword puzzle. I swore acid rain came out his pores if that pencil went missing.

Mornings were not a time to be boisterous. Noise or commotion made him grouchy. I had learned that the hard way one time, when Wyeth gave my knee a horse-bite at breakfast. The tablecloth concealed the fact that he started it. Father shouted at me for kicking and shrieking, while my brother got off scot-free, the weasel.

But none of that mattered now. Two weeks ago, Father had left us.

I peeked around the wall. “Bird-brain,” I chided myself. No need to act all grownup-like. After a few deep breaths, I settled quietly into my place at the breakfast table.

Mama stood basking in sunlight by the kitchen sink. Her slender body leaned against the counter. Hot water from the faucet formed a swirling mist that steamed up the window. Wasting hot water in our household was a mortal sin, but she seemed unconcerned and lost in thought. I stared at her beautiful silhouette.

Extending her right leg with pointed toes, she lifted her opposing arm with ballet gracefulness and stretched to her limit, as if offering God an invisible gift. After a moment, her arm descended gently back to her side, with hand and fingers floating down like a dove. The sweep of her arm completed a circle.

Then, with one knee raised, she made a slow pirouette like the tiny ballerina that revolved in my jewelry box. Steam billowed around her in the light. Her eyes were closed, her cheeks pink and glistening. She appeared to be dancing in some imaginary place.

I watched, leaning toward her in my seat, wanting to be wherever she was. Then her eyes caught mine. Her poise deflated. She turned and shut off the water. “There you are.” She blinked over and over and appeared embarrassed. The skin below her eyes was shiny and wet.

My cheeks felt hot. It seemed as though I’d interrupted a private moment. I stirred Tang into the cold water in my favorite Flintstones glass and splashed some milk on my cereal. “Where are the boys?” I asked, trying to sound normal.

“Wy had to walk Tuck to Indian Guides.”

She meant in Father’s place, but didn’t say so.

“Iris.” Mama squeezed my shoulder as she opened the fridge. “You can’t wear those thongs, remember?”

Father had said all sandals were “inapt” for school, and Mama had to back him up. I’d look up the word later, but I knew it meant a big fat “no.” Summer school should be different, especially on the very last day. Wearing flip-flops was part of summertime itself and second only to going barefoot. Father seemed to have rules about every doggone thing, and sometimes the twinge of defiance felt better than a joyless life.

“But, Mama…” I pleaded, “He’s gone, so why not?”

She gave me the ain’t-no-way look. “Besides,” she added, “It’s cool and wet from the storm last night.”

I slumped my shoulders.

“Go on now. Grab those new sneakers that your…” Her voice trailed off. She probably didn’t want to mention my father’s name.

I stood after spooning my last bite, glaring at her. With a sad smile, she tenderly reeled my stiff body into the sanctuary of her soft chest. I surrendered, though anger rumbled inside. My eyes watered. I shut them hard, wishing Mama and I could both twirl with the lightheartedness of dancers. Pressing my nose into her blouse, I lingered there, soothed by her clean sheet smell.

“I’m sorry Rissy,” she whispered.

Defying my father had consequences. We didn’t talk about it. I glanced at our embrace in the hall mirror. Tears spilled over her lower lids. She nuzzled my head.

After a minute, I pulled away and stuffed the dumb white Keds into my backpack. I let the screen door slam extra loud and clomped down the front steps. At the end of the driveway, I looked over my shoulder. Mama stood silently in the doorway, tying her apron. She raised a hand and fluttered her fingers. I ducked my chin, pretending not to see.

It was the summer of 1979 in Beaconsfield, Ohio. Wyeth and his friends were obsessed with “Rocky,” while girls my age were singing Bee Gees songs and watching Happy Dayson TV.

I loved our small town on the western shore of Lake Erie. Smack dab through the center of the township lay a wide and wooded area that separated rows of houses on either side. We called it the Middle Strip. I considered it my own personal forest, complete with dark scary places where I was quite sure a porcupine lived.

Most girls, especially the prissy ones, avoided the Strip on their way to school, because there wasn’t any clear path. I knew where to pick it up. Beyond the chokecherry patch, a certain cluster of weeping willows formed a concealing curtain. Pulling the branches aside, made the path magically appear. It flowed like a stream around the trees. Each curve and every exposed root was familiar.

I scrambled up the steep place. At the top, a rope lay fastened to the trunk of a thick oak tree. Holding the cord, I rappelled down the slope on the other side, releasing the rope’s stubby end to jump the last part of my descent.

After that, the trail veered right toward a swampy area teeming with new batches of mosquitoes. I always outran them, flapping my arms like a great blue heron. A shadowy, deep ravine yawned to the left, promising adventure for another day. Instead I followed the brightness overhead to a fragrant meadow where the Middle Strip ended near town. That morning, I stopped to put on my shoes.

My wet feet looked horribly white for early July. It was downright humiliating. I could’ve convinced Mama on the flip-flop thing had I really pressed her. Father wouldn’t even know. But then there was my teacher. Nothing got by her. Yesterday, my classmate Billy actually thought he could get away with keeping his frog, One-Eyed Jack, inside his desk. He needed to think again.

Tying the laces, I glanced back at my woods. How many times I had traveled through them on my way to Kensington School. Kindergarten, first, second, third, fourth, fifth and six…seven years added up. Over a thousand days worth.

And now summer school. I huffed and squinted. I wanted to be down at the park with the other kids watching city workers set up the fireworks. Instead I would be trapped in Reading Lab, where I wasn’t allowed to read one word at a time anymore. My eyes had to keep up with the moving red dot as it passed over sentences on a screen.

“Reeeeding Lab,” I said with deliberate irritation, in my best nasally tone. Tipping my head back, I looked at the great expanse of sky over the lake. Horsetail cloud wisps stretched across the blue heaven.

God, please help me pass the test. I’ll try to focus, I promise.

A knot tightened in my gut. If I didn’t pass, I might have to face one of Father’s lectures. He could return any moment. His stiff lips and clenched teeth made him seem like Sarge who was always angry with Beetle Bailey. If I failed, he’d probably lock me in my room and feed me liver and spinach until I finished the summer reading list. He’d remind me that girls who fall behind in school end up as hospital aides, cleaning up stinky old bedpans. A bubble of nausea rose in my throat.

Realizing the time, I jumped up to run the rest of the way. The safety guard had already left his post. Not a good sign. I passed Mike’s Delicatessen. No time for penny candy. At the red light, I crossed Lake Road, still sprinting.

As I mounted two steps at a time, my thighs started burning like the time I beat the three fastest boys at the hundred-yard dash. But it didn’t feel thrilling today. I slowed only to make a silly face at Anna Rae, who was imprisoned in remedial math class.

At the Reading Lab entrance, I stopped abruptly. My heart pounded in my ears. The mottled glass window in the door kept other students from spying on us. It didn’t really help. No matter how stealthily I came to or left the Lab, some kids knew everything and told everyone. They called us “Polka Dots” and referred to Reading Lab as the Dancing Dot Club.

Once, two pretty girls cornered Billy and me by the drinking fountain. “How brainless do you have to be to join the Club?” they tittered. They weren’t pretty on the inside. Their words smarted and made my eyes sting. After today, all that would end, and I’d disappear into the sea of students at junior high—that is, ifI passed the test.

“Iris? Is that you?’ My teacher’s shrill voice nailed me as I turned the black-enameled knob. “You’re late!”

“I’m sorry.” The door clicked behind me. The other students looked up in unison like a blob creature with twenty-eyes.

“Sorry?” Her voice rose another octave. “This is the thirdtime this week!”

I didn’t dare make eye contact. Without meaning to, I focused on her red gummy-worm lips. In fact, I usually looked at peoples’ mouths when they spoke and often missed what they said. Each mouth was unique, and a smile either made someone more attractive or just plain creepy.

Some people had beautiful teeth like white corn kernels lined up in a row. Their smiles made me feel warm all over. On the other hand, I’d seen more than one mouth with pointy vampire canines. Old people had teeth like porcelain sinks with hard water stains. And then there was poor Billy. His buckteeth were worse than any I knew. Father once said, “That boy could eat an peach through a picket fence.” I guess I noticed these things more than most, because my father was an orthodontist.

“Have you heard a single word I’ve said, young lady?” She stood too close to me.

I nodded.

“I rang your mother. She said you left in plenty of time.” My teacher had accidentally swiped some lipstick on her upper teeth. “What happens to you on the way to school?”

I swallowed hard, resisting the urge to laugh at her red teeth. My gut churned until I glanced at Billy. He slowly pointed to a white plastic container with holes poked in the lid. The humor of the moment vanished. One-Eyed Jack had been discovered.

“Are you daydreaming, Miss Somerset?”

“It won’t happen again,” I said, batting my eyelashes in earnest.

The more upset she became, the less chance I had of passing. I held my breath. She searched my face for insincerity with her built-in lie detector. One of her painted-on eyebrows rose higher than the other. Finally she turned tail and strutted back to her desk.

“Miss Iris…today is your last chance to finish up before the holiday. If you don’t pass the exam this time, you’ll be back for second session after the Fourth. Now, wouldn’t you rather be swimming like, say, Mister One-Eye here?” She glanced at the frog containment bucket.

“Yes ma’am.”

Muffled laughter circulated the room. Billy quickly curved his face away, straining his lips to cover his teeth.

“Well, get to it then.” She handed me the final exam.

I scurried to my desk. Reading comprehension was not my weakness. I even collected big, sophisticated words. My problem was speed. So I skimmed and wrote my answers like a maniac, glancing at the clock every few minutes. I could feel her eyes watching me. She always caught the cheaters. My right foot tapped impulsively, and I nearly slipped off my chair when the timer buzzed. She snatched our papers straight away.

The long silence of waiting for her to grade them was the worst part. Sunlight moved from my desk to Billy’s. He dozed, resting his head on his folded arms. A small line of drool trickled from his mouth and looked like melted gold in the sunshine.

I cracked all my knuckles twice. Then I counted hooks by the coatroom. I looked over. My teacher was still grading. On my fingers, I calculated the number of words in the Star-Spangled Banner, but got stuck on “perilous night,” trying to determine if “peril us” was one word or two.

“Iris Somerset?” My teacher rose from her squeaky chair and walked to my desk. “It’s a small miracle, but you have passed.”

Leaping out of my seat, I threw my arms around her thick waist. It felt like the moment I knew I could swim underwater and not drown. She promptly handed me the summer reading list. I hoisted my backpack over my shoulder and charged out of the room. I couldn’t wait to tell Anna Rae my big news.

The bell sounded. I planted my feet by her classroom door, shifting my weight left and right. Anna raised a wait-a-minute finger. Perturbed, I strolled outside by the parking lot to linger in the shade of an apple tree. I kicked off my new shoes and stretched out my toes in the cool grass. Hanging on a low branch, I looked around the schoolyard and started my farewells.

“Goodbye merry-go-round. Goodbye jungle-gym.” I felt happy and sad about it. “Goodbye swings and tether ball. See you later, bike rack.” What a strange feeling to leave everything I knew so well. I’d miss Bike Safety Week, when we all decorated our bikes with streamers and balloons and wore outlandish hats.

“Outlaaandish.” I let the fabulous word roll off my tongue. “Goodbye tall slide and swinging bridge.” Anna Rae still hadn’t come.

I looked at the open area on the playground and remembered the school carnival, especially the Cake Walk. My father said it was too easy, hence the name. I wasn’t sure what hencemeant. All I knew was if the carousel music started up and you stepped from one square to the next long enough, they handed you a pan of brownies or a blueberry pie just like that! Billy had to spend nineteen tickets one year, but refused to go home without some kind of baked goods.

Warm air wafted from the sizzling asphalt. Most of the summer school students were well on their way home now. The playground seemed unusually quiet. A light wind toyed with the swings.

A tiny white butterfly hopscotched from leaf to leaf on the young apple tree. I extended my fingers, but it darted out of reach. With feathery wings, it floated off in a puff of air. I’d remember it clearly, like a recurring dream, because it happened on the last day of my childhood.

Your mom is dead, I heard in my mind. It was a clear, calm voice. But she’s okay.

Watch the 3 minute book trailer here.