I happened to be in the second row. Only a few dozen people usually came to the evening service. The worship music provided a space of solace, quieting the rush of the day. With my eyes closed, I listened, waiting for anything the Holy Spirit might say.

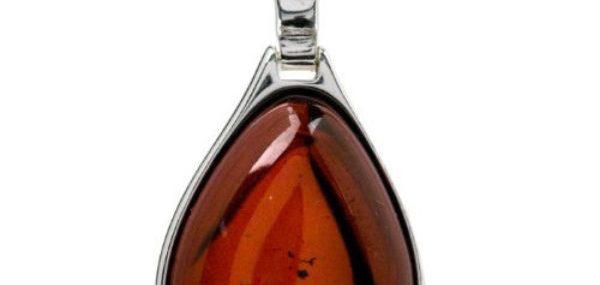

On the screen of my mind, I saw a woman wearing a large amber-colored stone in the shape of a teardrop. Too heavy to be jewelry, it seemed like a burden around her neck. The image was distinct, but fleeting. After a few seconds, it vanished. Had I really seen something?

On the screen of my mind, I saw a woman wearing a large amber-colored stone in the shape of a teardrop. Too heavy to be jewelry, it seemed like a burden around her neck. The image was distinct, but fleeting. After a few seconds, it vanished. Had I really seen something?

And then a phrase interrupted my thoughts…a weight of deep sorrow.

The music ended, and the pastor asked if God had given any impressions that might encourage everyone. I stalled. Hearing God for others was a new concept to me. After a few people shared, I drew a deep breath and raised my hand. I described the heavy stone and how it seemed more like a yoke than a necklace. My voice sounded shaky.

“And what do you think it represents?” the pastor asked.

“An amber teardrop…the color, the shape—maybe something from the past,” I offered.

“Something that’s keeping someone in continual sadness…a weight of deep sorrow.”

“Something that’s keeping someone in continual sadness…a weight of deep sorrow.”

The pastor gazed at the people in the rows behind me. “Does that mean anything to anyone?” His tone was kind.

I lowered my head slightly. The room went quiet. Perhaps it had just been my own imagination—making something from nothing. I felt a little foolish. No one responded, and blood rushed to my face. As the service continued, I avoided eye contact.

Several days later, my phone rang. Continue reading